By James Bradley, Little-Brown

Ths is the true story of the events in the lives of a handful of very young flyboys (WWII pilots and airmen) in the waning days of WWII in their march toward Japan’s home islands; the prices paid and the lives forever lost or changed. One of those flyboys was a 19 year old future President of the United States, George H. W. Bush.

Bush piloted one of four Grumman TBM Avenger aircraft from VT-51 that attacked the Japanese installations on Chichijima. His crew for the mission, which occurred on September 2, 1944, included Radioman Second Class John Delaney and Lieutenant Junior Grade William White. During their attack, the Avengers encountered intense anti-aircraft fire; Bush’s aircraft was hit by flak and his engine caught on fire. Despite his plane being on fire, Bush completed his attack and released bombs over his target, scoring several damaging hits. With his engine afire, Bush flew several miles from the island, where he and one other crew member on the TBM Avenger bailed out of the aircraft; the other man’s parachute did not open. It has not been determined which man bailed out with Bush as both Delaney and White were killed as a result of the battle. Bush waited for four hours in an inflated raft, while several fighters circled protectively overhead until he was rescued by the lifeguard submarine USS Finback.

Future President Bush flew 58 combat missions and received the Distinguished Flying Cross, three Air Medals, and a Presidential Unit Citation (U.S.S. San Jacinto). While you may not have agreed with his politics, you have to give the man credit for his remarkable bravery and dedication to duty. President Bush’s adventures were only a small part of this interesting book, yet an impressive part.

The rest of the book tells the stories of the ordeals of other young flyboys who weren’t as fortunate as Lt. (jg) Bush. They were captured, systematically tortured, eventually executed, then suffered the ultimate indignity… they were butchered and eaten by a handful of sick, misguided Japanese officers.

Mr. Bradley sympathetically and poignantly describes the small-town teenage backgrounds and aspirations of several of the American flyboys, and how they came to enlist in the Navy. He also interviewed several aged, repentant Japanese veterans who were willing to tell how they were brainwashed and forced into barbarous acts because of the Japanese military culture of obeying without question.

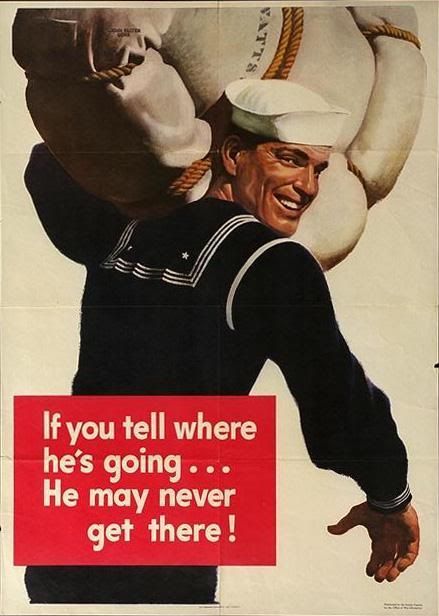

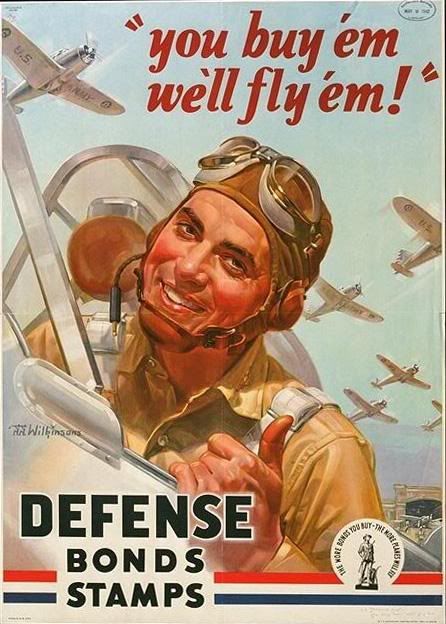

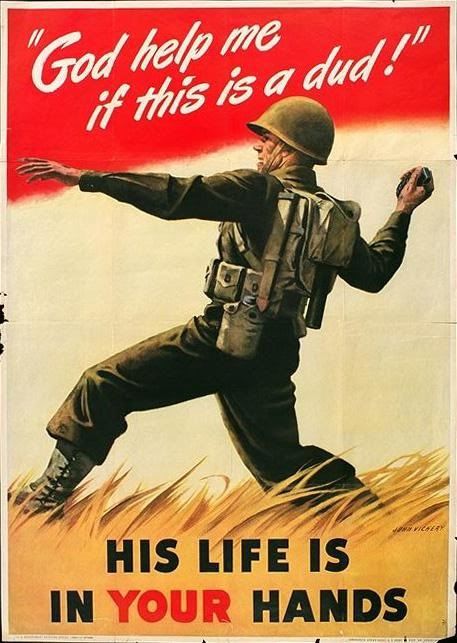

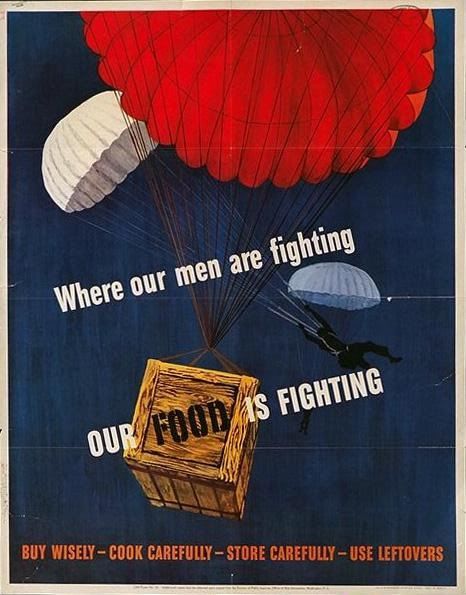

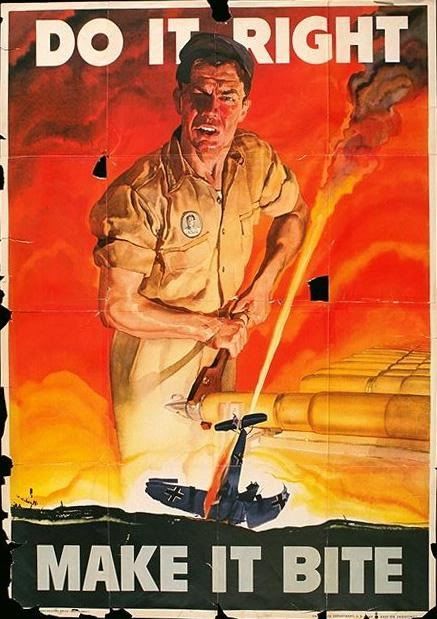

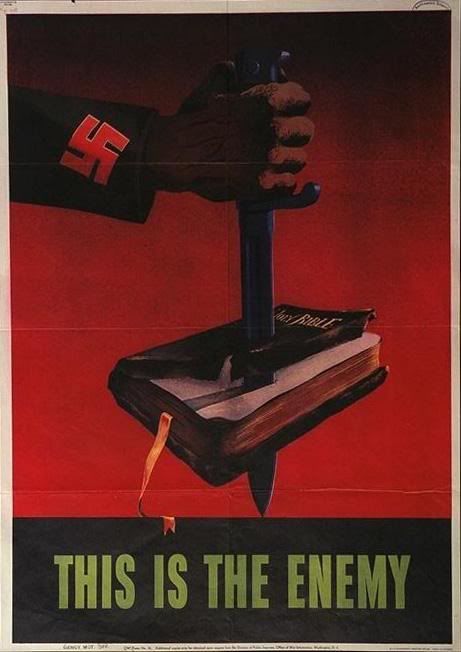

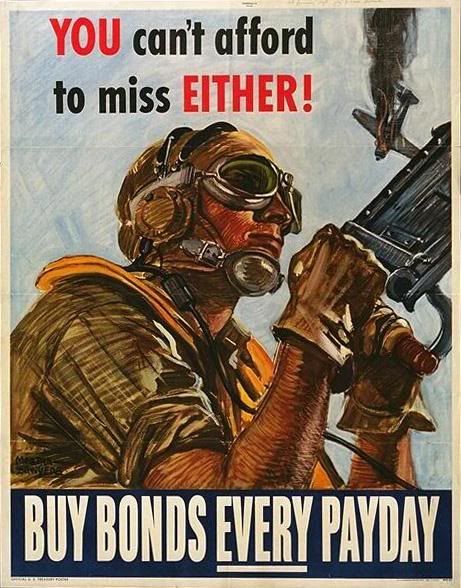

Additionally, it documents Japan's rise to power from 1849 to 1941, analyzes the rise of the airplane in warfare, and the military establishment's failure to heed the 1920s warnings of General Billy Mitchell that the American military build up its air power. The book analyzes various cruelties, hypocrisies, and war crimes of the Japanese and its government. It compares the atrocities Japanese troops committed on a large scale against Chinese civilians, with similar atrocities committed by American forces against Filipinos during and after the Spanish-American War, and earlier by American troops against native American Indians. Both the American and Japanese populaces were arrogantly indoctrinated that their national cultures were uniquely superior, which gave them the right to impose those cultures through imperialism on other weaker countries, whose people were viewed as subhuman.

As U.S. Marines in 1945 invaded Iwo Jima some 150 miles away, U.S. warplanes bombed the small communications outpost on Chichi Jima. While Iwo Jima had Japanese forces numbering 22,000, Chichi Jima's forces numbered 25,000. Additionally, Iwo Jima has flat areas suitable for a naval invasion, while Chichi Jima's geography included hilly terrains and unsuitable coasts. According to one Marine (who Bradley does not identify), "Iwo was hell. Chichi would have been impossible." Assumedly, it is because of this that U.S. pilots, known as "Flyboys", were needed to neutralize Chichi's defenses.

Nine crewmen survived after being shot down in the raid. One was picked up by the American submarine USS Finback. His name was Lieutenant George H. W. Bush, who later became the forty-first President of the United States. The others were captured by the Japanese and were executed and partially eaten as POWs, a fact that remained hidden until much later. Senior Japanese Army Officers hosted a Sake party for their Navy counterparts where the livers of American POW's were roasted and served as an appetizer. The Navy officers subsequently reciprocated by hosting a party where they butchered and served their own American POW's.

The book also documents Japanese cannibalization of not only the livers of freshly-killed prisoners, but also the cannibalization-for-sustenance of living prisoners over the course of several days, amputating limbs only as needed to keep the meat fresh in the harsh jungle environment. It also cites cannibalisim of Allied soldiers killed in action and of Japanese dead, wounded and by lot drawings.

These atrocities on Chichi-jima, were discovered in late 1945 and was investigated as part of the war crimes trials. In 1946, 30 Japanese soldiers were court-martialed on Guam and five officers (Maj. Matoba, Gen. Tachibana, Adm. Mori, Capt. Yoshii, and Dr. Teraki) were found guilty and hanged. All of the enlisted men were released within eight years.

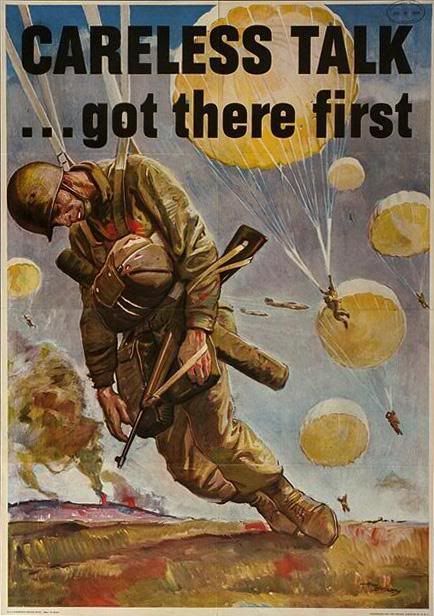

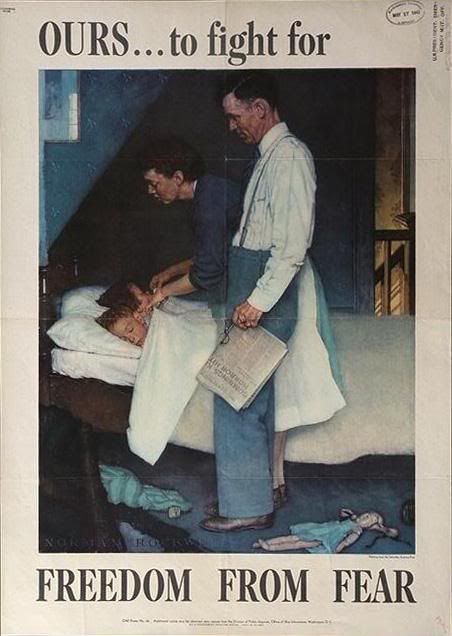

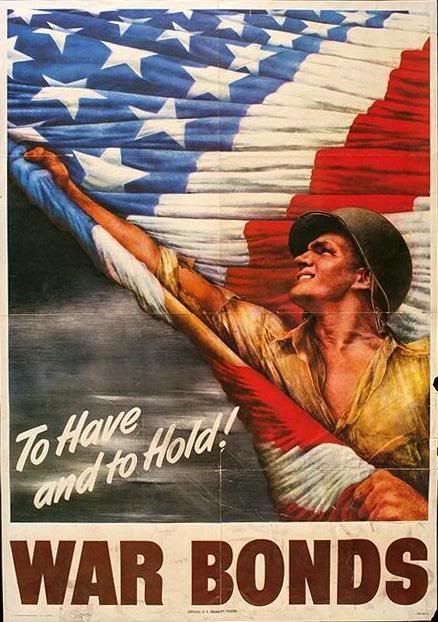

DisturbingSteve Hopkins, April 23, 2004Some will expect a story similar to "Flags of Our Fathers", but while a major part of Flyboys describes the courage of nine airmen who were shot down over the island, parts of the book will disturb or disgust some. Ethnocentric propaganda led both Japanese and American soldiers to consider the other as subhuman, leading many soldiers to despicable acts of torture, mutilation, and murder. Here’s an excerpt from the beginning of chapter 14 “No Surrender,” pp. 202-210:

Meet the expectations of your family and home community by making effort upon effort, always mindful of the honor of your name. If alive, do not suffer the disgrace of becoming a prisoner; in death, do not leave behind a name soiled by misdeeds.

- “Imperial Japanese Army Field Service Code”

In the European war, Germany did not surrender until Allied troops invaded its heart. But Japan would be defeated by Flyboys. The beginning of the end for Japan came on February 16, 1945.

On that Friday morning, the largest and most powerful naval attack force ever assembled, with more than twelve hundred planes, launched the first carrier raid on Tokyo since Jimmy Doolittle’s almost three years before.

It was a dangerous mission. Three days earlier, the air group commander on the USS Randolph had assembled all his Flyboys and announced, “Fellows, we’re on our way to Tokyo.” There was a moment of silence as the thought sunk in. Then the Flyboys broke out in loud cheers and applause. A moment later, a pilot turned to Bill Bruce and said, “My God, why am I clapping?”

That wintery day’s weather was murky, cloudy, windy, rough, cold, and wet. Flyboys like Bill Hazlehurst and Floyd Hall now appreciated all the damp flying they had done in Oregon.

The strike force lifted off early, plane after plane aloft with clockwork precision. Gunner Robert Akerblom did not fly that day, but he listened for news of his buddies’ progress. “Our ship piped a Japanese radio station through the loudspeakers,” Robert said. “Our first wave was supposed to hit Tokyo at six A.M. At exactly six A.M. they went off the air. We cheered.”

The Flyboys came in low, within antiaircraft range, and they took a heating. “Charlie Crommelin had over two hundred holes in his plane when he returned,” remembered fighter pilot Alfred Bolduc. “He had fifty-four holes in one gas tank.”

With so many planes over Tokyo that day, there were close calls. Fighter pilot M.W. Smith was strafing a train at an altitude of one hundred feet. “The fellow behind me shot his rocket right as I was going over that train,” Smith recalled. “He shot three holes as big as fists in both of my wings.”

The Japanese were surprised and unprepared. As a result, the carrier planes wreaked havoc on factories, shipyards, supply depots, and railroad yards. But bombing the Japanese mainland still brought a special terror. “We were scared,” said Hazlehurst. “It was disconcerting bombing Japan in part because there wasn’t open water to ditch in. You had to crash over land, and that meant you’d probably be captured.”

Charlie Brown was caught when his two-seater SB2C Helldiver was shot down near Tokyo. “We were bombing a factory,” he told me later. “We got hit; the engine was on fire. I saw a lake and made a water landing. As the plane was sinking, my crewman, J. D. Richards, was already in the life raft.” A farmer in a rowboat came out. Charlie and J. D. got into his boat. When they reached shore, another farmer Swung a club at Charlie’s head. “If he had hit me,” Charlie said, “he would have killed me.” Some Japanese soldiers appeared with a thick rope. “Oh, my God!” thought J. D. “It’s a lynching!” But the soldiers merely tied their prisoners together and marched them along a road. The procession would stop from time to time to allow women to beat the flyers with their geta — wooden shoes.

“Americans would be hitting just as hard if the situation was reversed,” Charlie said with a chuckle years later. “Emotions run high in the immediate area; people get upset when they’re bombed.”

Eventually, the party made its way to a railroad station. His captors took Charlie outside and made him kneel in the dirt and lean forward. “I had seen the photo of the Australian pilot about to be beheaded,” Charlie said. “Someone shoved me so my head was parallel with the ground. Then I heard sharp orders. I thought I was about to have my head cut off.”

But Charlie Brown would live to see another day.

Because the weather worsened around Tokyo on February 17, the carrier force headed south to pound Iwo Jima. Then they sailed to bomb Chichi Jima the next day.

On a cold Sunday morning, February 18, five Flyboys awoke ready to tackle their first combat missions. This was the day they had prepared for. In the month they had been at sea, they had had plenty of time to think about what that first taste of combat would be like. Now they were about to learn.

On the USS Randolph, pilot Floyd Hall would wing into action with his gunner, Glenn Frazier, and his radioman. Marve Mershon. On the nearby USS Bennington, radioman Jimmy Dye and gunner Grady York readied for their flight. Jimmy, Glenn, Marve, and Grady were all just nineteen years old. Floyd must have been one of the “old men” to them, because he was already twenty-four.

The boys were briefed on the day’s target, the airfields and radio stations on Chichi Jima. “Chichi Jima was a mean place,” said pilot Phil Perabo. “They had very good gunners there. When you hit Chichi, you were hitting a valley between two mountains.”

Fellow pilots Leland Holdren and Fred Rohlfing would fly into battle with Floyd that day. “Floyd, Fred, and I were a division of three,” Leland told me decades later. “This strike on Chichi was our first time in battle. We were greenhorns. You can imagine our anxiety.”

The winter sun did not rise until 7:12 A.M. on the morning of February 18, 1945. The USS Randolph began launching her planes at 10:54 A.M. The plane carrying Floyd, Glenn, and Marve was in the last group and launched after noon. They flew off into rainy, overcast skies.

Over on the USS Bennington, Jimmy Dye and Grady York were in their ready room being briefed on the same target. They would fly that day with pilot Bob King. “Our mission that day,” remembered Ralph Sengewalt, “was to bomb Chichi Jima’s small airstrip. They said we’d have limited opposition.”

February 18 in the Pacific was February 17 back home, and it marked two years to the day since Jimmy had enlisted. “We hadn’t been in cold climates until then,” Vince Carnazza remembered. “I had a black navy-issue sweater and Jimmy asked if he could borrow it. I gave it to him and said, ‘If I don’t get that sweater back, it’s your ass.’”

As they were headed out the door, Jimmy did something that Ralph Sengewalt will never forget. “Jimmy stopped at the door,” Ralph told me, “turned around, and with a smile, tossed his wallet to someone who was remaining behind. As he did it he called out, ‘Just in case I don’t come back, see to it that my mom and dad get this.’”

Kidding was one thing, but Flyboys almost never spoke so directly about death.

“When Jimmy said that,” Ralph recalled, “I had a strange feeling then and there. We never talked about not coming back.”

The assault two days earlier on Tokyo had been considered dangerous. but that day’s strike against Chichi Jima was anticipated to be relatively easy. a “milk run.” That’s why so many of the inexperienced airmen, like Bob King, Jimmy, and Grady, were heading out. But Jimmy must have had a sixth sense about the danger that awaited him. And radioman Ken Meredith learned that Grady had had his qualms too.

“When Grady and I shook hands on the flight deck,” Ken recalled, “he said. ‘I’m really scared.’ Grady always smiled when he talked. But at that moment he wasn’t smiling. Just then I felt Grady had a premonition. Even at that young age. I could feel it.”

Jimmy had tossed his wallet, but he did keep something for good luck that day. His girlfriend, Gloria Nields, later told me: “In the last letter I got from Jimmy he wrote, ‘I am flying off now with your white scarf on.

With that, the three American boys took off in their Avenger, pilot King. radioman Jimmy, and gunner Grady. Two of the three had signaled that this flight held special danger for them. King, also on his first combat flight, had not expressed any qualms. Only one of them would return.

The briefers had been wrong. The antiaircraft opposition was fierce that day.

“The antiaircraft fire was very heavy and very accurate,” said gunner William Hale. “There was black smoke everywhere, and we were getting bounced around with the concussion of the shells. I was facing aft with a pair of machine guns in my hands, looking for something to shoot at and wishing we could get the hell out of there.”

“It was overcast over the island,” remembered pilot Dan Samuel-son. “There was a hole in the clouds. A lot of the planes were going through that hole, and the Japanese gunners just plugged that hole with antiaircraft fire.”

One after another, the carrier pilots made their glide-bombing runs over Chichi Jima. Pilots Leland Hoidren, Fred Rohifing, and Floyd Hall — the “division of three” — circled above, waiting their turn.

“The most dangerous time is when you’re just hanging out, going slow,” said Robert Akerbiom. “Once you’re in the dive, you feel the speed and it relieves the tension.”

“We had to keep circling until the others made their dives,” Leland Hoidren said. “As you circle, you fly away from the optimum point from which to make your dive. If you dive relatively straight down over the target, you go in fast. But we were circling wide, and when it came time to make our dives, we dove in a less severe angle and didn’t generate as much speed as the guys before us.”

Leland began his dive into the flak with Fred Rohlfing and Floyd following behind. “When the antiaircraft fire comes up,” said fighter pilot Alfred Bolduc, “you see little red dots. When they get closer, they’re about the size of a baseball bat diameter. They’re coming at you by the hundreds.”

Two of those hundreds of red dots found their mark: Both Fred’s and Floyd’s planes were hit. Rohifing’s Avenger burst into flame and he, radioman Carrol Hall, and gunner Joe Notary never made it out.

Floyd’s plane did not catch fire, but it was fatally damaged and it was all he could do to make a safe water landing. Leland had flown off at the completion of his run, and since Floyd’s was the last plane, no one saw him or his crew land in the water. Letters from the navy to the parents of the three downed boys would later say that the probabilitY of their having survived the landing “was extremely low.”

But Floyd, Marve, and Glenn made it out of the plane safely and inflated their Mae Wests. They were wet, cold, and scared, but they were alive. They had landed between Chichi Jima and Ani Jima, a small uninhabited spit of land hardly big enough to have its own name. For some reason, Glenn split off from the other two and made his way to Ani Jima, while Floyd and Marve swam to Chichi Jima.

Floyd and Marve were now in the same general area that George Bush had found himself in six months earlier, though George had landed a bit farther out. Soldiers standing on the same cliffs where Nobuaki Iwatake had observed George’s rescue now saw Floyd and Marve in the water. Fisherman Maikawa Fukuichiro and Warrant Officer Saburo Soya were told to bring the Americans in. They paddled out about a hundred yards and found Floyd and Marve in the frigid water, ~almost half paralyzed and.. . on the point of sinking,” as Fukuichiro later recalled. “Their lips were blue and they looked cold.”

On the beach, the boys were allowed to warm themselves by a fire. Floyd was dressed in his one-piece flight suit and Marve was down to his white woolen long johns. Warrant Officer Soya told Fukuichiro to phone the headquarters of the 308th Battalion. The officer on the other end of the line ordered the flyers brought to the 308th, which would get credit for their capture.

At the 308th Battalion headquarters, the soldiers searched the prisoners and relieved Floyd of his pistol and Marve of his survival knife. These trophies were dispatched to Major Matoba.

But soon everyone on the island had to take cover once again. More waves of Flyboys were approaching. Floyd and Marve were bundled into an air-raid shelter.

Major Matoba retreated to his cave. As the falling bombs exploded in the sunshine outside, Matoba examined Floyd’s pistol and Marve’s knife. In the blackness, the major ran his hands over the Flyboys’ possessions as he drank and thought.

The swarms of carrier planes kept the island hopping that day.

“The February eighteenth raids were the fiercest air raids we experienced,” said antiaircraft gunner Usaki. “During the day about a thousand planes raided the island. As antiaircraft personnel, we were almost always at our battle stations and at night we also had to go to battle stations. We were very tired and every chance we got we slept in the quarters but stayed on the alert.”

The gunners were tired but dedicated. “We often had to eat our meals at our positions,” said Lieutenant Jitsuro Suyeyoshi. To the Flyboys, it seemed the emperor’s gunners didn’t pause for a bite. “There was so much flak, you could walk on it,” said Robert Akerbiom. Ralph Sengewait added, “It looked like every tree on the island was firing at us.”

And still the Flyboys came. Pilot Jesse Naul was flying behind Bob Cosbie’s plane, which in turn was to the right of Bob King’s Avenger, with Jimmy Dye and Grady York aboard. Jesse later told me what happened:

We came in at about nine thousand feet and we were getting ready to go into our dive. I was behind Cosbie’s plane. Suddenly, antiaircraft fire shot Cosbie’s right wing off. His plane went into a clockwise spin, spinning clockwise down toward the right, where his wing had been.

Cosbie’s plane flipped upside down and went sideways. It slammed into King’s plane. Cosbie’s left wing hit King’s plane between the turret and the vertical stabilizer. At the same time, Cosbie’s propeller hit King’s left wing and chewed off four feet of it.

King’s plane then went into a spin. King thought they would crash, so he told his crew to bail out. Jimmy and Grady bailed out. My crew yelled, “We see two chutes.”

King had his seat belt off, fixing to bail out, and to his surprise, he got the plane straight. He “caught it,” meaning he caught the spin and righted the plane. He kept flying.

As Grady and Jimmy bailed out, Cosbie’s Avenger went into a fatal spin. Cosbie, gunner Lou Gerig, and radioman Gil Reynolds never made it out. Jesse Naul speculated on what their last minutes might have been like:

Cosbie went into his spin at nine to ten thousand. His plane just spun and spun. Let’s say they were all alive when the plane went into that spin. Even though they were healthy American males, the centrifugal force would have pinned them to the wails and they wouldn’t have been able to get out.

If they were conscious, they knew what was happening and were fighting to get out. They’d be trying to unhook their seat belts and pop the doors off, but they wouldn’t have been able to get out of their seats.

When a loaded seventeen-thousand-pound plane is spinning, it creates a lot of force. It’s like a saucer at an amusement park that is spinning and pinning you back. It’s the same thing. The force of the spin would force them to remain in the position they were in when they started going down. Finally, they smacked into the water and that was it.

Jimmy and Grady floated down in the midst of exploding shells. ~Their chutes were surrounded by antiaircraft bursts,” recalled Joe Bonn. “1 dismissed them as shot up, dead.” But amazingly, the two crewmen landed safely just off shore.

“We flew down to drop them a life raft,” Ralph Sengewalt said, “but we didn’t drop it because we could see Jimmy and Grady in knee-deep water, walking toward the shore. We thought they’d be prisoners and they’d be safe — at least that was our hope.”

Now there were four Flyboys in Japanese hands on Chichi Jima — Floyd Hall, Marve Mershon. Jimmy Dye, and Grady York. Glenn Frazier was huddled in the bushes across the channel on uninhabited Ani Jima.

Floyd and Marve were held at the 308th Battalion headquarters for the rest of the day and overnight. Jimmy and Grady were captured by the 275th Battalion and taken to General Tachibana’s headquarters.

Captain Kimitomi Nishiyotsutsuji remembered that General Tachiharm encouraged anyone who wanted to beat the two bound nineteenyear-olds to do so. The general further warned that anyone who protected the boys by putting them in an air-raid shelter, or was lenient with them in any way, would face his wrath.

The next day, Monday, February 19, Jimmy and Grady were taken to Major Yoshitaka Hone’s headquarters. Major Hone could speak some English and he intet-rogated them. Glenn remained hidden in the bushes on Ani Jima. At night he must have shivered in the winter cold. He had a canteen full of water, no food, and only a little hope.

Early in the morning of the nineteenth, Floyd and Marve were taken from the 308th Battalion to General Tachibana’s headquarters, with a Stop to visit Lieutenant Jitsuro Suyeyoshi’s regiment. Suyeyoshi and the 308th both had a claim on the prisoners and they would later discuss who got to kill which one.

Floyd and Marve were tied up outside a guardhouse for three and One half hours, from 6:30 A.M. to 10:00 A.M. There, anyone who Wanted to absorb some Yamato damashii kicked and slapped the two defenseless boys.

Lieutenant Suyeyoshi admired the way the two Flyboys stoically endured their punishment. He ordered his men to assemble in front of the prisoners. “I offered them a drink of whiskey from my hip flask and a cigarette” Suyeyoshi said, “and then I turned around to the enlisted men in the crowd and told them, ‘These two flyers were working for their country and they are brave men, and I expect all of you to take an example from them.’”

But respect did not mean mercy. American bombs had killed some of Suyeyoshi’s men the day before and he wanted revenge. Later that afternoon, Suyeyoshi spoke to Matoba about the casualties and the major promised retribution. “Lieutenant Suyeyoshi wanted a flyer to execute in order to show his men that they were personally responsible for shooting down a plane or a flyer, and to give them more fighting spirit and to build morale,” Matoba said.

Floyd and Marve were loaded back into a truck and taken to Tachibana’s headquarters so the general could get a few licks in. But before he had a chance, an air-raid siren sounded and Tachibana turned to scurry to his protective cave. One soldier moved toward Floyd and Marve to untie them and bring them into a shelter. General Tachibana noticed and barked. “Why are you fooling around there? We do not care if they die or not.”

Later that day. Floyd and Marve were moved to Major Hone’s headquarters for interrogation~ where they joined Jimmy and Grady.

Floyd and Marve had flown off the USS Randolph, Jimmy and Grady belonged to the USS Bennington. Here they would meet for the first time, tied up and watched by guards. They were four kichiku in Japanese hands — four Flyboys in big trouble.

Bradley noted at the end of the book that proceeds from the sale of Flyboys have been used for scholarships for American high school and college students to study in Japan. From understanding, the events recounted in Flyboys are less likely to reoccur. In the spirit of achieving understanding, even with discomfort, I recommend reading Flyboys from cover to cover.

Sorties Into Hell: The Hidden War on Chichi Jimahttp://www.armchairgeneral.com/wordpress/wp-content/bookreviews/sih.gif

http://burruss.blogspot.com/2007/07/of-war.html

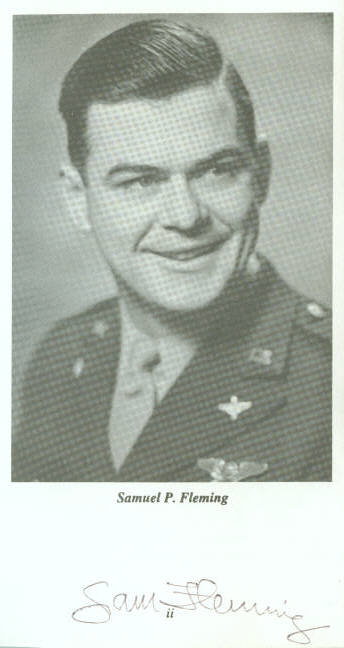

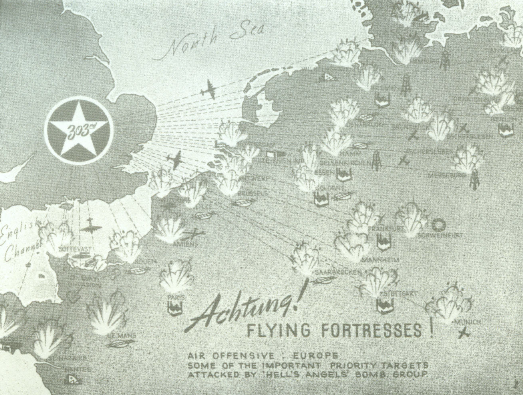

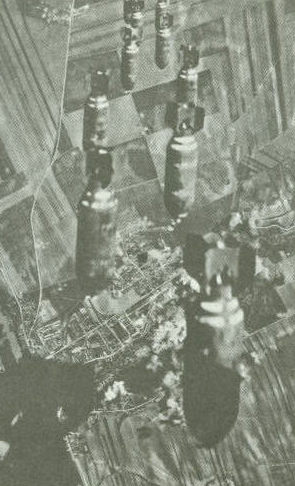

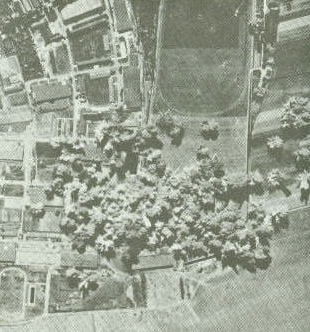

Fleming remembers the campaign vividly. With losses high on both sides, the life of a bomber crew was estimated at 15 missions.

Fleming remembers the campaign vividly. With losses high on both sides, the life of a bomber crew was estimated at 15 missions.

Several of the missions sixteen B-25B bombers are visible. That in the foreground is tail #40-2261, which was mission plane #7, piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Ted W. Lawson. The next plane is tail #40-2242, mission plane #8, piloted by Captain Edwards J. York. Both aircraft attacked targets in the Tokyo area.

Several of the missions sixteen B-25B bombers are visible. That in the foreground is tail #40-2261, which was mission plane #7, piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Ted W. Lawson. The next plane is tail #40-2242, mission plane #8, piloted by Captain Edwards J. York. Both aircraft attacked targets in the Tokyo area.  USAAF aircrewmen preparing .50 caliber machine gun ammunition on the flight deck of USS Hornet while the carrier was steaming toward the mission's launching point. Three of their B-25B bombers are visible. That in the upper left is tail #40-2298, mission plane #6, piloted by Lieutnenant Dean E. Hallmark. That in top center is tail #40-2283. It was mission plane #5, piloted by Captain david M. Jones. Lt. Hallmark, captured by the Japanese in China, was executed by them at Shanghai on 15 October 1.

USAAF aircrewmen preparing .50 caliber machine gun ammunition on the flight deck of USS Hornet while the carrier was steaming toward the mission's launching point. Three of their B-25B bombers are visible. That in the upper left is tail #40-2298, mission plane #6, piloted by Lieutnenant Dean E. Hallmark. That in top center is tail #40-2283. It was mission plane #5, piloted by Captain david M. Jones. Lt. Hallmark, captured by the Japanese in China, was executed by them at Shanghai on 15 October 1. Such a complicated and dangerous mission called for a combat leader who was an inspiring commander, a methodical thinker who could anticipate and solve myriad problems, a scientific mind who could weight the odds, and a strong personality who could bull his way through the layers of somnalent bureaucracy. Only one person came to mind. He was none other than the Babe Ruth of Flyboys, the irrepressible Jimmy Doolittle.

Such a complicated and dangerous mission called for a combat leader who was an inspiring commander, a methodical thinker who could anticipate and solve myriad problems, a scientific mind who could weight the odds, and a strong personality who could bull his way through the layers of somnalent bureaucracy. Only one person came to mind. He was none other than the Babe Ruth of Flyboys, the irrepressible Jimmy Doolittle. At the age of 45, American's preeminent Flyboy was as old as flying itself. Jimmy had "won nearly every aviation trophy there was." A fearless daredevil, a crowd-pleasing barnstormer, Jimmy had been generating headlines and thrilling world audiences with his acronautical aerobatics for twenty years. Jimmy regularly set and then broke international racing records. He had been the first to fly coast to coast in less than 24 hours and then first to do it in less than 12. Jimmy was a short, muscular fireplug of a man with a confident grin above his cleft chin. His nose was a little crooked from having been broken on his road to becoming a boxing champion. He was just 5 feet 4 inches tall and never weighed more thatn 145 pounds, but he was a giant who reached the clouds.

At the age of 45, American's preeminent Flyboy was as old as flying itself. Jimmy had "won nearly every aviation trophy there was." A fearless daredevil, a crowd-pleasing barnstormer, Jimmy had been generating headlines and thrilling world audiences with his acronautical aerobatics for twenty years. Jimmy regularly set and then broke international racing records. He had been the first to fly coast to coast in less than 24 hours and then first to do it in less than 12. Jimmy was a short, muscular fireplug of a man with a confident grin above his cleft chin. His nose was a little crooked from having been broken on his road to becoming a boxing champion. He was just 5 feet 4 inches tall and never weighed more thatn 145 pounds, but he was a giant who reached the clouds.

In the large meeting room the air was abuzz when the great little man himself walked in and announced, "Doolittle is my name." They knew exactly who he was as he was already a legend. They knew they were in for something big and that this mission was very important if he was involved in it.

In the large meeting room the air was abuzz when the great little man himself walked in and announced, "Doolittle is my name." They knew exactly who he was as he was already a legend. They knew they were in for something big and that this mission was very important if he was involved in it.  Lileutenant Colonel James. H. Doolittle (left front), leader of the attacking force, and Captain Marc A. Mitscher, Commanding Officer of USS Hornet pose with a 500-pound bomb and USAAF aircrew members.

Lileutenant Colonel James. H. Doolittle (left front), leader of the attacking force, and Captain Marc A. Mitscher, Commanding Officer of USS Hornet pose with a 500-pound bomb and USAAF aircrew members. As the Hornet headed for history, a typhoon-force wind buffeted the ships. Howling winds and sheeting sea spray had deckhands crawling across the deck on all fours to keep from being washed overboard.

As the Hornet headed for history, a typhoon-force wind buffeted the ships. Howling winds and sheeting sea spray had deckhands crawling across the deck on all fours to keep from being washed overboard.  USS Nashville firing her 6"/47 main battery guns at a Japanese picket boat encountered by the raid task force.

USS Nashville firing her 6"/47 main battery guns at a Japanese picket boat encountered by the raid task force. The plane at right has tail #40-2282. It is mission plane #4, piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Everett W. Holstrom, Jr. during the raid, in which it attacked targets in Tokyo. Note protective cover over its gun turret, and wooden dummy guns mounted in its tail cone. The plane at left is warming up its engines, as was done periodically during voyage.

The plane at right has tail #40-2282. It is mission plane #4, piloted by 2nd Lieutenant Everett W. Holstrom, Jr. during the raid, in which it attacked targets in Tokyo. Note protective cover over its gun turret, and wooden dummy guns mounted in its tail cone. The plane at left is warming up its engines, as was done periodically during voyage. USS Hornet as seen from the USS Enterprise.

USS Hornet as seen from the USS Enterprise. Doolittle's plane taking off from the USS Hornet at the start of the raid, 18 April 1942.

Doolittle's plane taking off from the USS Hornet at the start of the raid, 18 April 1942. Unique view of Doolittle's plane taking off from the USS Hornet.

Unique view of Doolittle's plane taking off from the USS Hornet.

After flying the B-17 over an enemy airfield, a German pilot named Franz Stigler was ordered to take off and shoot down the B-17. When he got near the B-17, he could not believe his eyes. In his words, he 'had never seen a plane in such a bad state'. The tail and rear section was severely damaged, and the tail gunner wounded. The top gunner was all over the top of the fuselage. The nose was smashed and there were holes everywhere.

After flying the B-17 over an enemy airfield, a German pilot named Franz Stigler was ordered to take off and shoot down the B-17. When he got near the B-17, he could not believe his eyes. In his words, he 'had never seen a plane in such a bad state'. The tail and rear section was severely damaged, and the tail gunner wounded. The top gunner was all over the top of the fuselage. The nose was smashed and there were holes everywhere.  Aware that they had no idea where they were going, Franz waved at Charlie to turn 180 degrees. Franz escorted and guided the stricken plane to, and slightly over, the North Sea towards England . He then saluted Charlie Brown and turned away, back to Europe . When Franz landed he told the CO that the plane had been shot down over the sea, and never told the truth to anybody. Charlie Brown and the remains of his crew told all at their briefing, but were ordered never to talk about it.

Aware that they had no idea where they were going, Franz waved at Charlie to turn 180 degrees. Franz escorted and guided the stricken plane to, and slightly over, the North Sea towards England . He then saluted Charlie Brown and turned away, back to Europe . When Franz landed he told the CO that the plane had been shot down over the sea, and never told the truth to anybody. Charlie Brown and the remains of his crew told all at their briefing, but were ordered never to talk about it.

Bush piloted one of four Grumman TBM Avenger aircraft from VT-51 that attacked the Japanese installations on Chichijima. His crew for the mission, which occurred on September 2, 1944, included Radioman Second Class John Delaney and Lieutenant Junior Grade William White. During their attack, the Avengers encountered intense anti-aircraft fire; Bush’s aircraft was hit by flak and his engine caught on fire. Despite his plane being on fire, Bush completed his attack and released bombs over his target, scoring several damaging hits. With his engine afire, Bush flew several miles from the island, where he and one other crew member on the TBM Avenger bailed out of the aircraft; the other man’s parachute did not open. It has not been determined which man bailed out with Bush as both Delaney and White were killed as a result of the battle. Bush waited for four hours in an inflated raft, while several fighters circled protectively overhead until he was rescued by the lifeguard submarine USS Finback.

Bush piloted one of four Grumman TBM Avenger aircraft from VT-51 that attacked the Japanese installations on Chichijima. His crew for the mission, which occurred on September 2, 1944, included Radioman Second Class John Delaney and Lieutenant Junior Grade William White. During their attack, the Avengers encountered intense anti-aircraft fire; Bush’s aircraft was hit by flak and his engine caught on fire. Despite his plane being on fire, Bush completed his attack and released bombs over his target, scoring several damaging hits. With his engine afire, Bush flew several miles from the island, where he and one other crew member on the TBM Avenger bailed out of the aircraft; the other man’s parachute did not open. It has not been determined which man bailed out with Bush as both Delaney and White were killed as a result of the battle. Bush waited for four hours in an inflated raft, while several fighters circled protectively overhead until he was rescued by the lifeguard submarine USS Finback. Future President Bush flew 58 combat missions and received the Distinguished Flying Cross, three Air Medals, and a Presidential Unit Citation (U.S.S. San Jacinto). While you may not have agreed with his politics, you have to give the man credit for his remarkable bravery and dedication to duty. President Bush’s adventures were only a small part of this interesting book, yet an impressive part.

Future President Bush flew 58 combat missions and received the Distinguished Flying Cross, three Air Medals, and a Presidential Unit Citation (U.S.S. San Jacinto). While you may not have agreed with his politics, you have to give the man credit for his remarkable bravery and dedication to duty. President Bush’s adventures were only a small part of this interesting book, yet an impressive part.